April 13, 2019

In Harold and the Purple Crayon,” a children’s book from 1955, the intrepid hero, a sturdy toddler, decides to go for a walk in the moonlight. There is no moon, and so, with his purple crayon, Harold draws one, and then decides to draw a straight path to walk upon. When this leads him nowhere, he follows his crayon—under the moon’s watchful eye—through a series of adventures, conjuring a field, a forest, an apple tree, a nasty dragon, an ocean, a sailboat, a beach, a picnic lunch of pie, a moose and a porcupine to eat it, a mountain to climb, a balloon to ferry him down it, a house, a front yard, a city full of windows, and a policeman to point the way home. Then, finally, he draws his bedroom window around the moon, draws his bed, draws himself under the covers, drops the pen and goes to sleep.

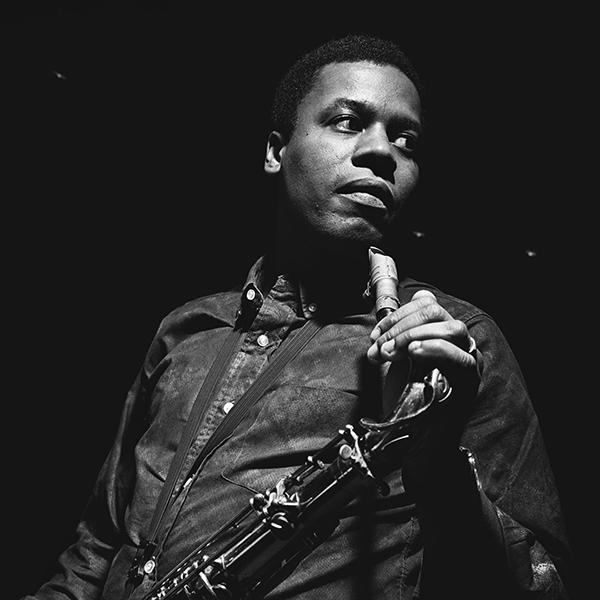

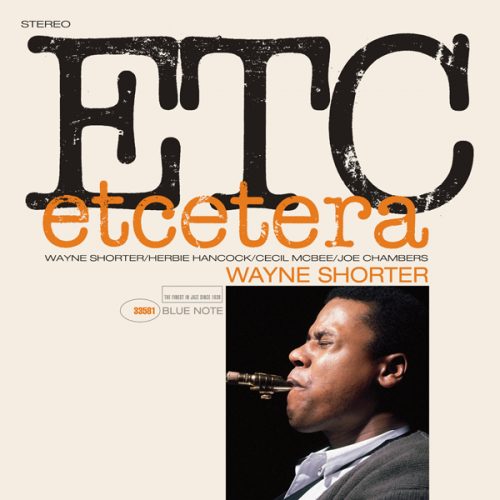

This synesthetic process is not unlike what Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Cecil McBee, and Joe Chambers did at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio on June 14, 1965, when they made Etcetera, Shorter’s fifth recording for Blue Note. Like each of Shorter’s other Blue Note sessions from that era, it was a one-shot affair. “There was nothing developmental as a band,” he told his biographer Michelle Mercer. “A recording was just one movie, and then the next was another movie, in a kind of dream away from Miles.”

The notion of an imaginary screenplay in notes and tones suits the ambiance of this exceptional date. Each piece evokes a fantasy world, tells a story with a beginning, a middle and an end upon which the protagonists improvise, creating lines that assume a life of their own and following them wherever they choose. As Hancock put it thirty-seven years later, “The world is Wayne’s stage; he can grab a metaphor from almost anything in life.”

Perhaps that cinematic, episodic quality is one reason why Etcetera, which would not be released until fifteen years after it was recorded, resonates so deeply. Another is the humanity of Shorter’s instrumental voice, efflorescent in the quartet setting, emotional, hardcore, expressing the same passion, vulnerability and free spirit that suffuses his pieces.

Consider the kaleidoscopic emotional range conveyed on the noirish title track, on which the leader and Hancock, already close friends after nine months together with Miles, offer soliloquies conveying ecstasy, torment, and angst, navigating the tricky harmonic terrain with melodies that meander through, around, and in synch with Joe Chambers’ roiling, orchestrative, funky beats. On the meditative “Penelope,” dedicated perhaps to the wife of Odysseus or to a real, live woman (Shorter doesn’t say), the composer channels his inner Strayhorn, while on “Toy Tune,” a mid-tempo swinger that doesn’t settle on a key center, Shorter offers a master class on building tension over multiple choruses. On Gil Evans’ “Barracudas,” he uncorks a Coltrane-inflected declamation (Hancock’s response is equally intense) whose thematic coherence is undoubtedly informed by his year-earlier solo flight on Evans’ swirling arrangement of that piece on The Individualism of Gil Evans. Of “Indian Song,” an anthemic line propelled by Cecil McBee’s insistent bass vamp and Joe Chambers’ impeccable, surging, polyrhythmic 5/4 beat, Shorter further refracts Coltrane’s syntax and spirit into his own argot on a lengthy first section, before Hancock, himself a force of nature, completely changes the feel.

Perhaps another reason why Etcetera has become such a notable signpost is that, as much as any other Shorter album, it emblemizes an aspiration that Shorter stated in 2003, while traveling in Europe with his present quartet in the aftermath of the U.S. invasion of Iraq. “Music is a part of the struggle,” he said. “They talk about the unknown factor—they don’t know what’s going to happen. Why don’t we do that every night on stage? There’s no school, no university for the unknown. Music is mysterious. Everything is. The unexpected is what’s happening.”

—Ted Panken