September 1, 2023

In Blue Note Records: The Biography, the British jazz critic Richard Cook commends the work of Francis Wolff and Alfred Lion, co-founders of Blue Note, for recording Meade Lux Lewis, Albert Ammons and James P. Johnson, innovators of the boogie-woogie and stride piano styles. “These beautiful sessions,” Cook writes, “suggest that Blue Note might have gone on to compile a piano history of jazz.”

It’s a good point, and in fact, there are many under-appreciated pianists hiding in the Blue Note discography: Elmo Hope, Herbie Nichols, and Sonny Clark among them. Jack Wilson, too, is one of those pianists. He seems, however, even more obscure—which is odd, because he had a sensitive touch and a musical sensibility that seemed ideally geared toward commercial success, or at least popularity in the jazz world. Cook only mentions Wilson once in his Blue Note book, in passing, and the Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings doesn’t include him at all.

Wilson died in 2007, at the age of 71—unlike Hope, Nichols and Clark, who all passed in the 1960s. At an early age, Wilson was an accomplished pianist and sideman, performing with James Moody in 1953 and working with Dinah Washington later in the decade. If you want to get a sense of his style, there are many places to look—in 1963, he put out his first record as a leader The Jack Wilson Quartet featuring Roy Ayers on Atlantic. But the best examples of his work might be the three excellent records he made for Blue Note in the second half of the 1960s.

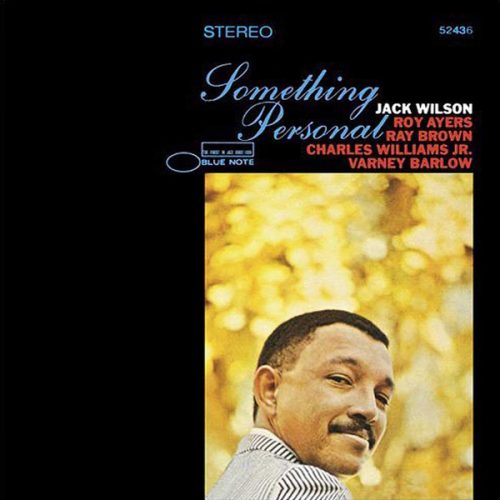

The first was Something Personal, from 1966, perhaps the most interesting of the three. With vibraphonist Roy Ayers joining Wilson once again, it’s got a chamber-like quality to it; some tracks might lead you to recall the work of the Modern Jazz Quartet, a band that featured the same instrumentation you’ll find here: piano, vibes, drums and bass. Except, on two tracks, Ray Brown plays cello and Charles “Buster” Williams Jr. walks the bass. (About that cello: It’s not an instrument you’ll see too often in a traditional jazz setting. But here, played pizzicato on the Wilson composition “Most Unsoulful Woman” and “The Sphinx,” written by Ornette Coleman, it’s lovely, unusual, and altogether refreshing.)

Easterly Winds, the second record Wilson made for Blue Note, a year later, features a front-line horn section of Jackie McLean on alto saxophone, Lee Morgan on trumpet, and Garnett Brown on trombone, with Bob Cranshaw on bass and Billy Higgins on drums. That’s a top-shelf hard bop line-up, and this is a quintessential hard bop album with tracks like the groovy lead-off number “Do It” and the hard-swinging “On Children” conjuring that instantly identifiable “Blue Note Sound.” Even with such exciting players, though, Wilson comes off as the most refined. With that in mind, it’s no surprise that the prettiest song—the ballad “A Time For Love,” by Johnny Mandel—puts Wilson into a trio context, so he can show us his gifts as a soloist and an interpreter of melody.

On Song for My Daughter, the last of his three Blue Note albums, Wilson places himself square in the middle of a lush-sounding string orchestra. It’s a fine record, with a good dose of Brazilian rhythm thrown in. The best moments happen when the rhythm section swings at a medium tempo, allowing Wilson take some very good and lyrical solos.

Listening to all three of these records, what really stands out—besides the obvious differences in instrumentation that make each one a unique artistic statement—is Wilson’s wonderful piano style, a constant throughout. You get the impression that at this point in his career, he knew what kind of pianist he wanted to be, and he had already gotten there. His approach sounds like a mix between Bud Powell and Horace Silver, with Gene Harris’ blues virtuosity thrown in for good measure. Not that he was imitating them; there’s a bounce in his touch that sets him apart from those musicians.

Obscurity is a fate that befalls many good jazz musicians who fit the bill of stylist more than innovator. Often, though, finding out what actually sets those kinds of musicians apart—what makes them special—can be one of the most rewarding and pleasurable aspects of listening to jazz. And there’s a lot of pleasure to be had from listening to the music of Jack Wilson, perhaps the most under-appreciated pianist in Blue Note’s wide-ranging discography.