January 25, 2015

“The impetus to do this record was the joy of collaboration and exploration,” says Jamie Cullum. “I didn’t know what it was going to be, but I loved this band, loved this producer, so we just booked some days in the studio and thought, ‘Well, let’s see what it becomes.’ And within thirty minutes, we had recorded ‘Don’t You Know,’ the Ray Charles song—the version on the album is how we sounded half an hour after meeting.”

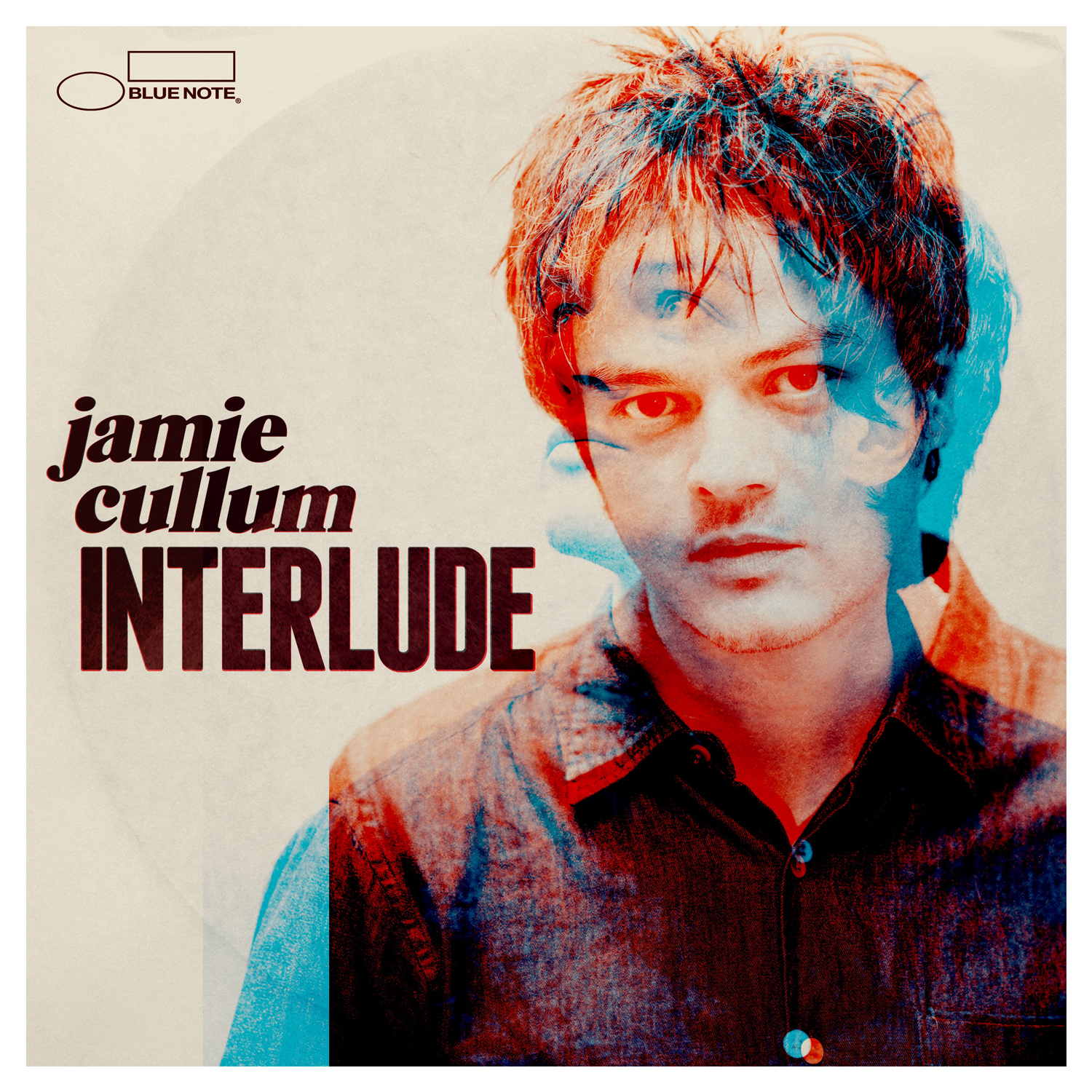

From there, it was off and running, and a mere three days later, the result was Interlude, the seventh studio album by the best-selling jazz artist in UK history. While the definition of “jazz” has been thrillingly fluid for Cullum, who is best known for blending genres and sounds with his original compositions, this project had its roots in the award-winning weekly show he hosts on BBC Radio 2, the most listened to jazz broadcast in all of Europe.

“After four years of presenting an hour of jazz to a new audience, I felt this burning need to make my own statement in that world,” says the singer and pianist. ”Listening to so many new records and new things, communicating my passion for the music, really inspired me—I found that I was coming home and putting jazz on again!”

One of the guests Cullum invited onto his show was London-based producer Ben Lamdin, who leads a band called Nostalgia 77. “When I met Ben,” he says, “I hadn’t realized how similar our backgrounds were—how we discovered jazz through drum and bass, and Beastie Boys and A Tribe Called Quest, and DJs like Gilles Peterson. So we hit it off, and I said to him, ‘I want to inhabit your world for two or three days, and let’s see what we come up with.’”

Within a few weeks, Cullum had joined up with the group in what he describes as its “hilarious but amazing studio behind a fish market.” They may not have known which direction they wanted to pursue, but—especially coming off of the adventurous 2013 album Momentum, which was produced in part by Jim Abbiss (Artic Monkeys, Adele) and Dan the Automator (Kasabian, DJ Shadow)—they had a sense that they wanted to go in a different direction.

“We are now very aware and encompassed by a ‘jazzy’ sound,” says Cullum. “Someone like Michael Buble has done incredibly well—amazing voice, recording brilliant songs with a real big band sound that people love. There’s Rod Stewart and lots of other people doing standards albums. But they all kind of slot into this Rat Pack area, which is exciting and musically adventurous and wonderful, but it’s a sound and a style that in some ways we’re all quite familiar with.

“As soon as you dial it back a few years, more to Boardwalk Empire, you get something that’s close to the blues, closer to the more original African-American experience, something with a bit more dirt to it. And then you jump past that era to the ‘60s and ‘70s, to the records Nina Simone was making, they’re like EDM records, or to what Alice Coltrane was doing, which are like Brian Eno records, and it’s all quite modern, particularly in the context of now.”

Cullum and Lamdin quickly started knocking song ideas back and forth (“we’re both crate-diggers,” says the singer, “record nerds joining the dots”). They ended up with a list that spanned an astonishing range of American music—from genuine standards (“Come Rain or Come Shine,” “My One and Only Love”) to hard-charging jazz tunes (the Dizzy Gillespie title track, Cannonball Adderly’s “Sack o’ Woe”) to literate contemporary pop songs (“The Seer’s Tower” by Sufjan Stevens, Randy Newman’s “Losing You”), and even a country classic, “Lovesick Blues,” popularized by Hank Williams.

“We didn’t want to choose things that were too obvious, but that didn’t prevent us from choosing songs we loved,” says Cullum. “We definitely wanted to have a real blues element to it, arrangements that spoke a bit more of the ‘30s and ‘40s—a little more harmonically knotty, where the singer was more part of the band instead of just fronting the band.”

They also settled on two songs that would showcase a couple of the most exciting young voices in music today. Cullum recorded Billie Holiday’s immortal “Good Morning Heartache” with Laura Mvula, and “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” (based on Nina Simone’s version rather than the Animals’ hit recording) with Gregory Porter. “I really wanted to tell an old story to new people,” Cullum says, “and I knew that by having them sing it would instantly be very current, very of-the-moment.”

All of the songs on Interlude were cut in the most old-school way, live in the studio, no separation, everyone playing at once. “We were recording in single takes—I don’t think anything went past three takes,” Cullum says. “I allowed myself to get lost in arrangements that I hadn’t done myself, to bounce off these musicians I didn’t know so well. And every musician in that room was better than me. Recording all in one room creates an immediacy that makes you aware of how you sound, and aware of delivering something that’s hopefully great every time.”

Cullum says that it was while cutting the Harold Arlen/Johnny Mercer composition “Out of This World,” in a swirling, mystical arrangement based on Alice Coltrane’s work, that he could feel himself entering new territory. “Recording that was just amazing,” he says. “That modal jazz zone the musicians were in is totally their bag, so getting to hear them play it that close, to be in the middle of it during a take that felt particularly spiritual and next level, was such a joy. I was so disappointed we got that in the first take, because I wanted to do it again!”

Cullum has been breaking musical boundaries since he self-released his first album, Heard It All Before, in 1999, while he was still studying at the University of Reading. Pointless Nostalgic (2002) was certified Gold in the U.K., and was followed by Twentysomething, which reached the Top 5 and was certified triple Platinum. In recent years, though, he has cut back on his touring to be able to spend more time at home with his two young children.

With Interlude, Cullum also got the opportunity to pursue another of his jazz-related passions; he took all the photographs that appear inside the album’s packaging. “One of the ways I fell in love with jazz in the first place is the iconography of it all,” he says. “Before I understood the music, I liked the pictures. I ended up going to film school and studied photography, and I’ve always taken photos. Since I made this record without the label knowing—I was out of a deal and didn’t know if anybody was putting it out—I thought, ‘I’ll take my own photos.’”

With this album, it feels like Jamie Cullum has turned on a creative faucet that will be hard to turn off. “I’m halfway through my next record already,” he says. “I’ve written about seven or eight songs, and making Interlude has really made me want to push this next one sonically a bit further, so it’s quite exciting.

“But we’ve also already got tentative dates for the end of next summer to do Interlude, Volume 2. I could never have done something like this ten years ago—I didn’t think I was good enough—but now it feels like something we’ll be able to do regularly.”