By Darcy James Argue

December 9, 2022

Donald Byrd’s ’70s records are awesome. Unlike most of his peers, Byrd made the transition to electric groove-based jazz successfully, and a big part of that success was his longtime association with the Mizell Brothers.

Larry and Fonce Mizell met Byrd while they were students at Howard University, where Byrd was on faculty. Larry earned a degree in electrical engineering and worked on the Apollo Lunar Module. Fonce went out to LA where he was a founding member of The Corporation, the Motown songwriting and production crew responsible for most of the Jackson 5’s hits, including “I Want You Back.” Larry eventually went out west to join his brother and together they founded Sky High Productions. The Mizells contributed to Byrd’s 1972 Ethiopian Nights, but their big breakthrough was Black Byrd, which became the best-selling Blue Note record of all time.

Larry and Fonce Mizell continued to produce all of DB’s 70’s output for Blue Note, including Street Lady (1973), Stepping into Tomorrow and Places and Spaces (both 1975) and Caricatures (1976). These Mizell-era Donald Byrd records were widely derided by jazz critics and by many of Byrd’s peers, who branded him an apostate for abandoning the acoustic hard bop style he helped define. Thad Jones (who wasn’t above arranging a funky O’Jays hit for his big band) told critic Leonard Feather: “Donald’s sellout was very obvious and there was nothing musically valid in what he did.” But Byrd’s 70’s records are seriously beloved by DJs and soul and disco aficionados, and have been widely sampled by hip-hop artists—if anything, Donald Byrd is probably held in higher esteem by them than he is by jazz fans.

It’s easy to hear why. The playing, writing, arranging, production, and recorded sound on these records is just brilliant, particularly on Stepping Into Tomorrow and Places and Spaces. The music is concise, soulful, and unpretentious, qualities a lot of other 1970s recordings by jazz artists could maybe have used a little more of. The rhythm section is anchored by the unstoppable team of bassist Chuck Rainey (best-known for his playing on Aretha Franklin’s Young, Gifted, and Black, plus all of Steely Dan’s best records) and drummer Harvey Mason (Headhunters, Brecker Brothers).

These records are master classes in rhythmic authority, and also in the kind of real-time rhythm section interaction jazz aficionados are supposed to hold in high esteem. The drums, bass, congas, rhythm guitars, and keyboards are all constantly embellishing around the basic rhythmic structure, trading fills, and responding creatively to one another, all without stepping on each other’s toes or getting in the way of the groove. This is the best kind of rhythm section playing: it’s selfless, un-showy, and relentlessly badass.

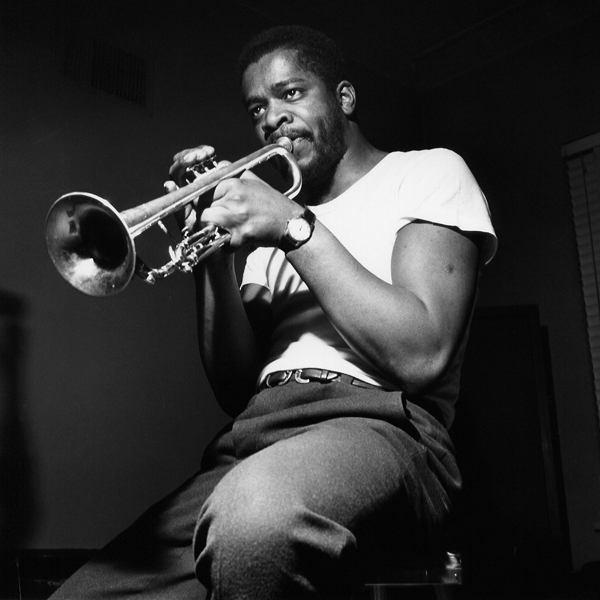

The tunes are full of inventive details, like the slyly dissonant bassline on “Stepping Into Tomorrow,” or how the apparently simple chord progression in “Change (Makes You Want To Hustle)” is inflected with a subtle harmonic twist in the turnaround. And Byrd himself is in fine form on all these records—his sound is dark and lyrical, his ideas are exuberantly inventive, and everything he plays sits beautifully in the pocket. And Byrd doesn’t just play—he also contributes lead vocals! So okay, no one’s going mistake him for Donny Hathaway, but you’ve got to give it up to him for putting himself out there to that degree. And seriously, he acquits himself just fine.

Donald Byrd’s 1970s records with the Mizells succeed because of the authentic and profound craft that went into their creation. They weren’t carelessly tossed-off in a crass attempt to try to cash in on current trends, they were meticulously shaped by master musicians at the very top of their game. They were made by artists who were engaged in a real conversation with contemporary musical culture, and even helped define it: “Change (Makes You Want To Hustle)” was a legitimate hit on discotheque dance floors. And the legacy and spirit of these groundbreaking recordings is alive and well.

Some of you may still be thinking, “Yes, but is it jazz?” To those people, I say, “Seriously? That is literally the least interesting question you could ask about this music.”