September 23, 2022

Charles Lloyd has long been a free spirit, master musician, and visionary. For more than six decades the legendary saxophonist and composer has loomed large over the music world, and at 84 years old he remains both at the height of his powers and as prolific as ever. Early on Lloyd saw how placing the improvised solo in interesting and original contexts could provoke greater freedom of expression and inspire creativity.

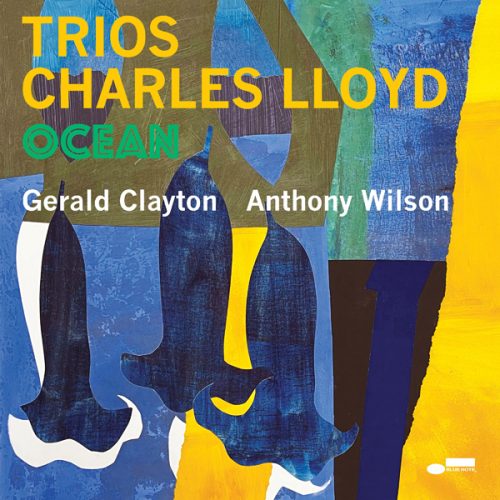

As a sound seeker, Lloyd’s restless creativity has perhaps found no greater manifestation than on his latest masterwork, an expansive project that encompasses three individual albums each presenting him in a different trio setting—a Trio of Trios. The first, Trios: Chapel, features Lloyd with guitarist Bill Frisell and bassist Thomas Morgan. The second, Trios: Ocean, with guitarist Anthony Wilson and pianist Gerald Clayton. The third, Trios: Sacred Thread, with guitarist Julian Lage and percussionist Zakir Hussain.

Lloyd once pointed out that his playing was a reflection of his life in real time. Perhaps this explains the emotional power of his playing, a soulful cry from the heart that argues for peace and beauty in a world becoming increasingly impatient with both. It’s why his saxophone tone, his signature in sound, is central to his art. “I’m trying to get a great sound, because when I think of all the great masters that went before, this kid in me still sees areas where I come up short and I continue to work on it,” he says. Unique and expressive, it’s what draws listeners into his music, shaping the emotive elements of his performances, from passionate intensity to sotto voce subtones, from which we construe meaning.

With good reason Lloyd’s playing has been described as lyrical, a style that is evocative of singing, expressing a subjective, personal point of view. Indeed, as a child he wanted to train as a singer, and today, when he plays a ballad, such as his recent recording of ‘Anthem’ by Leonard Cohen on Tone Poem, he has spoken of how knowing a song’s lyrics helps him add greater expressive weight to his playing. It is a reminder of music’s ancient connection with words and how melody frequently follows the meter and rhythm of speech patterns. Formalized a thousand years ago with the diatonicism of plainsong, music’s evolution through chromaticism to what has been called “the crisis in tonality” precipitated by Arnold Schoenberg, was mirrored in jazz in the space of just fifty years. So much has been accomplished in music that today, the search for the “always new” that propelled jazz through the twentieth century has given way to the realization to the once witty riposte by arch-modernist and surrealist Man Ray in the 1920s — “I can’t do something better than the old masters did, my only justification is to do something different.”

One way of achieving Man’s point of difference in jazz is changing the backdrop to the improviser’s art, since context has the effect of enhancing and transforming meaning — as Offred reminds us in Margaret Atwood’s Handmaiden’s Tale, “Context is all.” Atwood’s words could well be the leitmotif for Charles Lloyd’s career. It is something that he’s spent a lifetime exploring, for example, the quartets he led with pianists Keith Jarrett, Michel Petrucciani, Bobo Stenson, Geri Allen, and Jason Moran, each of whom was of a different poetic caste, helped shape the destiny of his music in different ways, each a wind of change that inspired new beginnings and new directions.

In later years this challenge deepened as Lloyd began experimenting with different instrumental combinations, each bringing a change of tone and texture to his music, such as a septet with vocalist Maria Farantouri plus his regular quartet augmented by lyra player Socratis Sinopoulos and second pianist Takis Farazis, with his groups The Marvels and Sangam, and latterly with his Trio of Trios project — three different trios of three different instrumental permutations each with strong yet simpatico musical personalities contributing to the ultimate destiny of the music.

The Ocean Trio, one of three configurations documented in the Trio of Trios trilogy, was recorded in the 150-year-old Lobero Theater, Santa Barbara, California, in Lloyd’s hometown (where he has played more than any venue, and more than any other artist). It was live streamed on September 9, 2020, during the first year of the global pandemic, so there is no audience. Lloyd was joined by Gerald Clayton on piano and Anthony Wilson on guitar, both sons of famous musician fathers — Clayton the son of West Coast bass legend John Clayton, while Anthony Wilson is the son of celebrated band leader, trumpeter, composer and arranger Gerald Wilson, in whose big band Lloyd once played when he moved from Memphis to study at the University of Southern California when in his teens.

Lloyd began his performance with an original, “Lonely One,” his saxophone entering on a zephyr-like breeze that sets the mood, key and tempo as Clayton and Wilson’s accompaniment coalesces around him. The mood is ruminative yet mysterious, suggestive of times lost — the shadow cast by the pandemic is a long one — but it also something more. We are all from somewhere, and part of the artist’s quest is to explore that somewhere, how it has shaped the inner person and what can be creatively channeled into the present. Feelings and moods are what this album is about — the introduction to “Hagar of the Inuits” feints and teases as it finds its way into a “blues tinged” groove with Wilson’s guitar solo, in particular, perfectly framing the moment.

The blues have always been woven into Lloyd’s musical vocabulary, its influence, sometimes overt, sometimes covert both occurring in “Jaramillo Blues,” which is dedicated to the painter, Virginia Jaramillo and her husband, sculptor Daniel Johnson, can be traced back through a precise timeline that leads back to his teens, playing alongside such blues masters Howlin’ Wolf, Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland and B. B. King. This is a blues of an optimistic hue — Clayton’s bright, rootless chords providing an introduction to Lloyd’s flute, who sets mood and tone of the performance.

“Kuan Yin” evolves from mysterious openings by Clayton, one hand inside the piano dampening lower strings creating a percussive from the lower keyboard where the destination of the song is unclear until a variation of a rhumba rhythm opens into minor key exoticism. Lloyd is at his most animated during this finale, while Clayton and Wilson capture his mood and intention perfectly. Clayton’s solo climaxes and, like a director’s soft dissolve, six notes from Lloyd brings the trio’s performance to a conclusion. Nothing more needed be said, but so too nothing can be taken away without destroying the narrative arc of the performance. It is complete, an aural photograph of a moment in time along Lloyd’s path into the heart of meaning.