April 7, 2016

One of the greatest trumpeters to ever play jazz, Freddie Hubbard was a dynamo, teeming with passion and imagination. His fervid hard bop playing matured into an original voice after he grew out of his Clifford Brown infatuation and emulation, garnering him the DownBeat New Star award in the magazine’s 1961 Critics Poll.

Once he moved from his hometown of Indianapolis to New York in 1958 at the age of 20, Freddie thrust himself into the thick of action on the hyperactive, hypercreative jazz scene, which often meant long club nights of multiple sets and heady blowing competition. He managed to not only stay in shape during the ‘60s, but he also found himself chosen to be a worthy contributor to classic jazz sessions by the titans of the genre at the time. A sampler: Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz; John Coltrane’s Olé Coltrane and Africa/Brass (and later Ascension); Eric Dolphy’s Out to Lunch; Herbie Hancock’s Maiden Voyage; Wayne Shorter’s Speak No Evil; and Oliver Nelson’s The Blues and the Abstract Truth. Freddie also jumped aboard Art Blakey’s fiery Jazz Messengers train in 1961, replacing Lee Morgan and linking up with Shorter as the band’s formidable frontline.

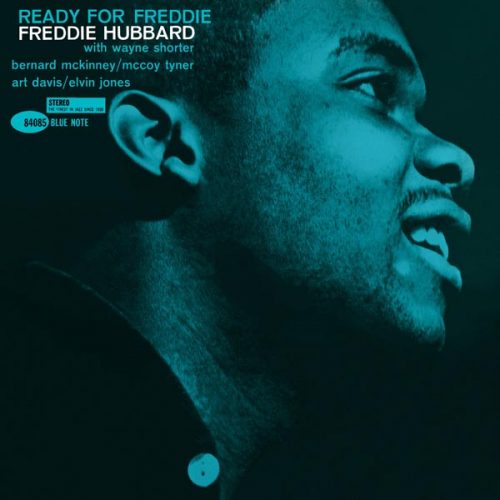

Freddie arguably became the most active trumpeter of the ‘60s era when his home base was Blue Note Records, both as a leader and as a session man. He recorded nine albums at the helm for the label and appeared on nearly thirty albums as a band member. His first three albums for Blue Note (1960’s Open Sesame and Goin’ Up; and 1961’s Hub Cap) served to introduce the new kid in town to the greater jazz world. But by the time he recorded his fourth date, Freddie was fully prepared to put on display his high-flying self. The apropos-titled Ready for Freddie—produced by Alfred Lion and recorded on August 21, 1961 at Rudy Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs, N.J., studio—certainly showcases the 24-year-old youngster geared up and prepared for the top-tier jazz life. In fact, Ready for Freddie jump-started the trumpeter’s career as a force to be reckoned with. He was truly ready and not to be denied.

The date features Freddie leading an unusual instrumental sextet that included Bernard McKinney on the mellow-toned euphonium, a tuba family instrument that was rare for jazz. Freddie knew Bernard (later known as Kiane Zawadi) from their days working with Slide Hampton’s octet. Odd as it was in that day, Freddie was breaking out and wanted to have that baritone-like tonal quality to blend with his horn and the urgent yet smooth tenor saxophone of Wayne Shorter. This was the first recording studio meeting of Wayne and Freddie, who had linked up a few days earlier in Blakey’s new sextet version of the Jazz Messengers for a live recording at the Village Vanguard.

The rhythm section was also comprised of youngsters that Freddie had worked with on Olé: pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Art Davis and drummer Elvin Jones. Looking back to that period, it’s remarkable that Freddie had enlisted a band with most of its members becoming top-drawer improvisers who would go down in jazz history heralded as significant figures.

Ready for Freddie opens with the uptempo “Arietis” (a Freddie original playing off his astrological sign Aries) with the trumpeter’s rapid-fire, lofty lines that reach peak after peak followed by Wayne’s down-to-earth sharp tenor swirls and spins, Bernard’s velvet-toned reflection and McCoy’s distinctive pianistic sparkle. That’s followed by Freddie’s gorgeous balladic trumpeting on the drum-brushed Victor Young beauty “Weaver of Dreams” where the leader accelerates midway to pleasant affect. Already making his compositional brilliance well-known in Blakey’s band, Wayne brings to this session “Marie Antoinette” (his fantasy of how fanciful life was like on the royal throne before the French Revolution’s guillotine climax) which he and Freddie deliver with a bounce and boom—Wayne playing brusque brass and light whimsy while Freddie smilingly skips through his chorus with emphatic notes.

Side 2 of the session opens with a tribute to bop’s founding father, Charlie Parker. While Freddie speeds with bop intensity on “Birdlike,” he’s also playing beyond the bebop genre on this rhythmic cooker that features well-developed choruses, not just blowing bouts—thus the “like” in the song title. The album closes with the striking and sober “Crisis,” written by the leader amidst the heightened Cold War tensions of the Soviet Union and the U.S. toying with the prospect of nuclear annihilation. It’s the longest track on the five-song album and also features Elvin letting rip with an intensive drum solo.

In the original line notes by Nat Hentoff written at the time of the session, he says that “Freddie will surely continue to develop…[and] he has already started to make a striking personal impact on the jazz scene.” The sentiment is stated in a hopeful way, noting how Freddie was “persistently searching.” But no doubt Nat could have never imagined the rich future that lay ahead for the youngster from Indianapolis. Ready for Freddie proved to be the launching pad for the trumpeter’s imminent career triumphs.