January 15, 2021

On the spectrum of jazz challenges, Wayne Shorter’s “Speak No Evil” appears to lean toward the easy side. The title track of the eminent saxophonist and composer’s 1964 masterpiece Speak No Evil sits in a comfortable and utterly approachable medium swing. Its primary theme is a series of long tones outlining placid, open-vista harmony. Its bridge resembles something from the notebook of Thelonious Monk – a simple staccato motif that stairsteps up and down, each phrase defined by strategic accents.

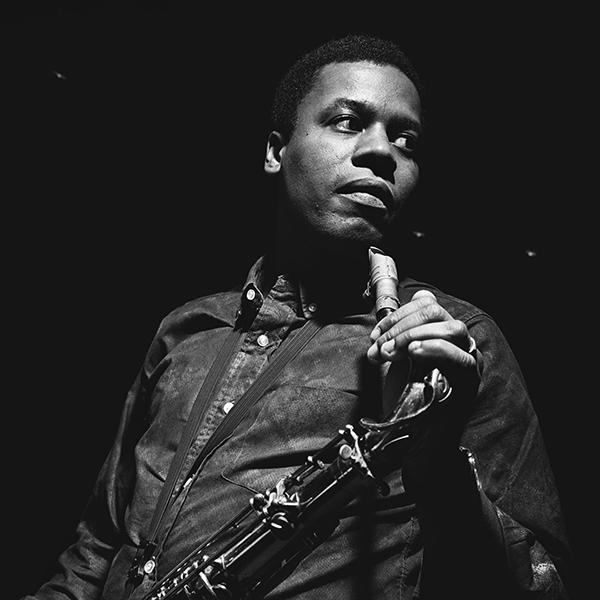

Yet as often happens in the music of Wayne Shorter, things are not entirely what they seem. There are layers. The notes of the melody tell one story; the chords nudge the musicians someplace else, a realm where theory lessons are of limited value and instinct matters more than intellect. To thrive in this place, the musicians have to relinquish the tricks of the jazz trade – the lightning-fast bebop runs, the killer licks they lean on to navigate chord changes. The tune, simple though it may be, comes with its own specific language – a trait it shares with many of Shorter’s pieces. Before diving into the conversation, the improviser has to discover the specific quirks of the form, its textures and temperament. How challenging is this? Even Shorter, who wrote the tune, sometimes struggles. He begins “Speak No Evil” by repeating a deftly tongued single note over and over, as though chopping his way into new territory. Shorter’s first few lines are simple declarations with a smidgen of blues in them – he’s not thinking about solo hijinks, he’s just trying to hang with the slalom course that is his creation. As he steers around tight curves, his lines coalesce into a kind of spontaneous lyricism – he’s singing through the horn, linking seemingly disconnected phrases into one (!) hauntingly memorable chorus. The subsequent soloists embrace his melody-first example when improvising: trumpeter Freddie Hubbard blows wistful then tender then fierce; pianist Herbie Hancock follows spry modal lines into quiet introspective corners.

This subtle “guiding” of soloists is a crucial component of Speak No Evil, and much of Wayne Shorter’s compositional output. The last of three monumental works Shorter recorded in 1964 (the others are Night Dreamer and Juju), this album frequently turns up on shortlists of essential jazz, and one reason is Shorter’s ability to coax those around him out of their comfort zones, and into new ways of playing. Shorter’s melodies encourage musicians to stretch, and so do his vividly imagined harmonic environments – playgrounds, really. No other jazz figure found such innovative ways to balance hard bop rhythmic fire against delicately loosened (yet, crucially, still tonal) harmony. And where some contemporaries built brainy maze-like contraptions, Shorter went straight for the heart, trusting that the poignancy he embedded in his structures would stir something similar within the soloists. The moods he explores here are deep and absorbing, far from typical jazz club fare: “Dance Cadaverous” offers a macabre tour of a haunted house (or, perhaps, a haunted mind), while the keening octaves of “Infant Eyes” sketch human vulnerability with a rare sustained empathy. Incredibly, these pieces become deeper and thicker in the solo passages, as each of the players gingerly endeavors to enhance the beauty already on the page.

That’s what every composer wants – the chance for the vague notions he scribbles on paper to take root, expand and blossom as music. Shorter managed that with astounding consistency over the years, creating a songbook that’s regularly described as the “mother lode” of jazz composition. That songbook has many riches – some are stone simple, some merely sound simple, and some are deceptively sophisticated and complex. It’s a vast trove of heady music, and the high-level sorcery at work within Speak No Evil is a great way to begin exploring it.