October 12, 2018

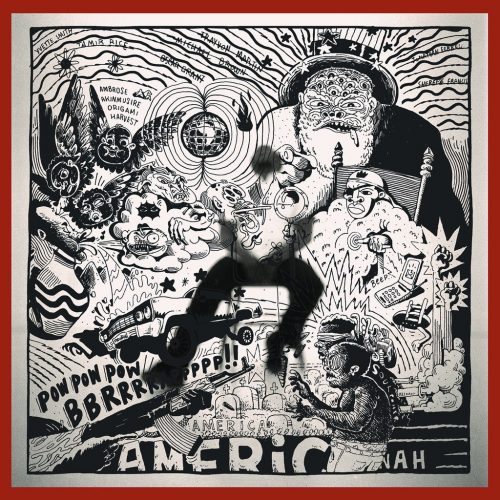

Composer and trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire‘s fourth studio album began with a challenge of sorts. It was a commission from curators Judd Greenstein of Manhattan’s Ecstatic Music Festival and Kate Nordstrum of St. Paul’s Liquid Music Series that began with Greenstein asking, “What’s the craziest idea you have?” Considering “challenge” and “crazy” are the order of the day, Akinmusire’s reply was right on time: “I wanted to do a project about extremes and putting things that are seemingly opposite right next to each other.” The result is Origami Harvest, a surprisingly fluid study in contrasts that—with help from New York’s beastly Mivos Quartet and art-rap expatriate Kool A.D.—pits contemporary classical wilding against deconstructed hip-hop, with bursts of left-field jazz, funk, spoken word, and soul.

That the album’s spirit evokes this era is no accident. These songs actively respond to societal divides, the way our politics hold us emotionally hostage, and the ever-growing list of black lives ended by structural racism. As with each of this Oakland native’s works—not least among them 2017’s assertive, unpredictable, double-length A Rift in Decorum: Live at the Village Vanguard—there’s exquisite beauty and superb artistry here, each track a world unto itself lithely traversing moods and modes. But there’s heft too, even in the title. “Origami,” says Akinmusire, “refers to the different ways black people, especially men, have to fold, whether in failure or to fit a mold. Then I had a son while writing this and I thought about these cycles repeating: Harvest.”

That tug-of-war between hope and dread is evident immediately. Opener “a blooming bloodfruit in a hoodie” is named in recognition of Trayvon Martin’s terrible death yet contains the album’s brightest tones and easiest grooves. Drummer Marcus Gilmore takes us from gentle rolls to head-nod beats, as regular collaborator Sam Harris plays tranquil piano and shimmering keys. Akinmusire blows sunshine while Kool A.D. rhymes from the pocket: “We are the universe learning to love itself, swirling in color and light.” Chaos lurks though—midway through, the rhythm section vacates, leaving the MC spitting out-of-place rap tropes (“Real hip-hop!”) over a melancholic Mivos. A brief return to a Soulquarian-style jam belies what’s coming.

“miracle and streetfight” begins in a flurry of drums, Gilmore evoking both a street-corner bucket solo and an avant-garde experiment in phasing. The rest of the band joins and finds a menacing loop for Kool A.D.’s musings, but now he’s unnerved, shouting, “America! Americana! America—nah! The big monster!” The only relief is guest Walter Smith III’s tenor saxophone, which arrives on a swell of synth bass. Mivos later carry us to a lush free-jazz session, and Akinmusire’s trumpet goes blue on the way out. Though emotions shift as quickly as the sonic landscape, themes emerge. Take “Americana / the garden waits for you to match her wildness,” a song built on choppy Reichian repetition that includes a hypnotic theremin-like keyboard solo and wild trap-inspired percussion.

“That one was about trying to bend time and space,” says Akinmusire, who chose to work with strings on Origami Harvest because of their proficiency in this area. “I was thinking about how in today’s political climate, we don’t ever have space to stop and take a breath. It’s like somebody has interrupted the path to peace in ourselves. The track is changing just enough that you can’t ignore it. You have to either turn it off or relax into it. I wanted to control how you feel time pass.”

Akinmusire is such a quickly evolving artist that his own past can feel distant, but it informs all of this. He grew up in North Oakland in the ‘80s. Dad, from Lagos, shared his immense work ethic and a cache of Nigerian records. Mom, from Mississippi, blasted Funkadelic and, on Sundays, young Ambrose’s favorite: Aretha Franklin, Amazing Grace. She’d keep his schedule packed to keep him out of trouble, but he found his own way to music at 2—he couldn’t stop banging on grandma’s piano, so he began lessons. Then came drums, trumpet, music camps, bands and workshops. Despite it being a rough era, Akinmusire says, “I grew up in a very black, culturally rich, proud Oakland.” One of his mentors was a former Black Panther.

That spirit remains. It was there when he was a teen prodigy hand-picked for Steve Coleman’s band. It drove him through his years at Manhattan School of Music, USC (for his master’s), and the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz, where he studied with Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter. It was there in 2007 when he won both the Monk and Carmine Caruso international jazz competitions before dropping his vividly hued debut Prelude: To Cora. When he moved back to New York for collaborations with the likes of Esperanza Spalding and Jason Moran, a Blue Note deal, and two increasingly adventurous LPs. And recently, in his appearance on Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, and in “Mae Mae,” his live tribute to imprisoned ’30s blues singer Mattie Mae Thomas.

Origami Harvest is Akinmusire’s first album since moving back to his hometown and he had protest in mind. You can hear it plainly on “Free, White and 21,” which doubles down on an Akinmusire tradition of reading the names of African Americans killed by police, or would-be vigilantes, over music. Versions of this appeared on 2011’s When the Heart Emerges Glistening and 2014’s The Imagined Savior Is Far Easier to Paint. Here, he wails and whistles the spiritual “Blood-Stained Banner” over a warped patriotic march. But his intent, he says, “Is exactly the same, and that’s the point. I want it to be kind of annoying, like, ‘Oh, he’s doing this again?’ It’s like, ‘Yeah, that’s how I feel. We’re still dealing with the same shit I was dealing with on my first Blue Note album.’”

That song, whose title was a popular catchphrase in pre-‘50s America, is preceded by the cooler “particle/spectra”—a stark classical piece that becomes a future-soul banger starring Oklahoma City singer LmbrJck_T—and followed by the furious closer “the lingering velocity of the dead’s ambitions.” Therein, Mivos lift their bows and saw wildly at one another as Akinmusire’s trumpet cries and sputters. When Gilmore joins there’s a sense of forward motion, hope, but Mivos soon undo that, deconstructing everything into cartoonish lurches, as if the song is trying to escape its own skin. Then comes a final breath as we’re delivered from anger, to pain and, finally, erasure. As Origami Harvest’s finale, it’s as powerful a statement as any of the words that come before.

It’s no wonder that after performing these songs live for the second time, at Ecstatic, Akinmusire was seized with the need to record them. He asked his collaborators if they could hit the studio the very next day and, miraculously, they agreed. It’d taken him a year to write, and the themes were too ripe, too now. “I was thinking a lot about the masculine and the feminine. High and low art. Free improvisation versus controlled calculation. American ghettos and American affluence,” says Akinmusire. “Originally, I thought I put them all so close together that it would highlight the fact that there isn’t as much space between these supposed extremes as we thought, but I don’t know if that’s actually the conclusion of it.” The answer, of course, is being written all around us.