June 10, 2020

The first note you hear on Ambrose Akinmusire’s fifth studio album on the tender spot of every calloused moment is his own—a somber yet vibrant tone that conveys jazz and the blues in equal measure. In years past, this wouldn’t be the case; Akinmusire is a bandleader who foregrounds collective improvisation. So to hear him take the lead on “Tide of Hyacinth” is a bold leap: Akinmusire not only asserts himself as one of the best trumpeters in the world, he’s using his voice to dissect the complexity of black life in America. Yet he isn’t trying to summon gloom, he’s unpacking it all. Through his trumpet comes the breath of a black man who’s seen the best and worst of the country, and harnesses it into 49 minutes of gorgeous, shape-shifting art.

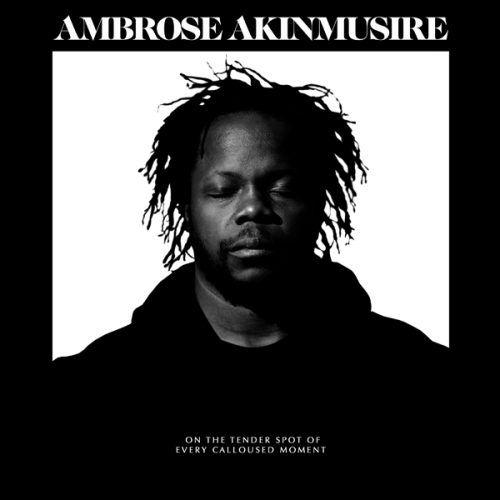

But that isn’t surprising if you’ve followed him to this point. on the tender spot of every calloused moment is the latest in a rich assembly of music he’s released, each album drawn from very real emotions and instances in his life. Where 2018’s Origami Harvest was a study in contrasts, on the tender spot is a study of the blues in a contemporary context. It continues a theme first established on his first Blue Note album, 2011’s When The Heart Emerges Glistening: On that cover, he has short hair and a cleanly shaven face. For this one, he has locks, facial hair, and a black hooded sweatshirt. “In a way, I was thinking about this as a sequel to my first record [on the label],” Akinmusire says. “I’m returning to the landmarks in my first album.”

Akinmusire grew up in North Oakland in the 1980s, in what he has called a “very black, culturally rich” neighborhood. After living in New York for 10 years and Los Angeles for three, he moved back to his hometown in 2016 and noticed how much it had changed. It simply wasn’t the same Oakland. But it’s the same thing in historically black cities throughout the U.S.; in places like Oakland, Brooklyn, and Washington, D.C., natives are being priced out of their homes due to rising rent. What’s left are new neighbors with no sense of the communities that preceded them. Akinmusire is speaking to that, to coming back home and feeling like a stranger in the place you grew up, where the newcomers see your black skin and assume you’re the one who doesn’t belong.

While on the tender spot scans as jazz, there’s a prevalent blues woven within the LP. It’s in the moonlit melancholy of “Yessss” and the gentle lullaby of “Cynical sideliners,” which, Akinmusire says, is a tongue-in-cheek ode to haters. Over light electric piano, vocalist Genevieve Artadi assures you it’s going to be fine—you’re the brave one; pay no attention to the naysayers. “You are you and they are they,” she sings. “You’ll be brave and they’ll be safe.” Then there’s a song like “reset (quiet victories & celebrated defeats),” a spacious and haunting procession doubling as a trumpet solo. Scant drums and piano chords fill the background; a complex sorrow permeates the mix. While creating this album, Akinmusire says he wrestled with conveying what the blues looks like in modern times: “The blues is about resilience.”

Much like his previous work, on the tender spot unpacks the feeling of “otherness” and what that means in a country with such a fraught racial history. In that way, it resembles Origami Harvest and 2014’s the imagined savior is far easier to paint. But where those records seethed, this one simmers; Akinmusire examines the past with pondering eyes and not a furrowed brow.

Indeed, on the tender spot navigates what it means to simply exist as a black person in America. Alongside drummer Justin Brown, pianist Sam Harris and upright bassist Harish Raghavan—bandmates for over a decade—Akinmusire delves into the internal strife of every person made to think they’re inferior. In a land where political leaders cater to the 1% and justice is reserved for fairer skin, there might be a notion to give up and make yourself smaller to fit in. Akinmusire is rebuking that notion: You don’t have to code-switch or conform to their rules. “You can be yourself and still be successful,” he says. “You don’t have to dance for people if you don’t want to dance.”

on the tender spot also eulogizes another great jazz trumpeter, Roy Hargrove, who died of cardiac arrest in 2018. In the late-1990s and early-2000s, Hargrove was a link between jazz, hip-hop and soul, and appeared on pivotal records by D’Angelo, Common and Erykah Badu while forming his own sonic hybrid. Hargrove’s death rattled the jazz community and Akinmusire himself. “I don’t think I would be alive if I hadn’t met him when I did,” he tweeted at the time. “I am extremely grateful I got to tell him as a grown man to his face.” In turn, the song “Roy,” which draws from the Baptist hymn The Lord’s Prayer, is an almost three-minute reflection near the album’s end. The song feels funereal—equally mournful and optimistic. “Roy was my dude!” Akinmusire says. “We’ve had so many different ways of relating from the age of 15 to 35.”

It all leads to the album’s chilling closer, “Hooded procession (read the names aloud),” which extends Akinmusire’s tradition of remembering the fallen. On When the Heart Emerges Glistening, he had “My Name is Oscar.” On the imagined savior he had “Rollcall For Those Absent,” where a child reads the names aloud: Amadou Diallo, Wendell Allen, Trayvon Martin and Timothy Russell, among others. On Origami’s “the lingering velocity of the dead’s ambitions,” the tribute was implied: In lieu of names being rattled off, the music itself expressed grief. The same goes for “Hooded procession,” where Akinmusire’s sullen keys land exquisitely. As it unfolds, the instrumental track begs for a new set of names to be spoken. That it doesn’t have words and still resonates is the trumpeter’s greatest asset: Across this and other albums, he’s able to say powerful things without saying anything at all.