Biography

From gospel and early R&B to soul and jazz to blues and straight-up pop, Lou Rawls was a consummate master of African-American vocal music whose versatility helped him adapt to the changing musical times over and over again while always remaining unmistakably himself. Blessed with a four-octave vocal range, Rawls’ smooth, classy elegance — sort of a cross between Sam Cooke and Nat King Cole — permeated nearly everything he sang, yet the fire of his early gospel days was never too far from the surface. He made his name as a crooner, first by singing jazz standards, then moving on to soul in the mid-’60s, and capped the most commercial phase of his career with a productive stint at Philadelphia International during the latter half of the ’70s. Even after his days as a chart presence were over, Rawls remained a highly visible figure on the American cultural landscape, pursuing an acting and voice-over career in addition to his continued concert appearances, and doing extensive charity work on behalf of the United Negro College Fund.

Louis Allen Rawls was born in Chicago on December 1, 1935, and was raised on the city’s south side by his grandmother. He sang in the choir at his Baptist church starting at age seven, and became interested in popular music as a teenager by attending shows at the Regal Theatre, with genre-crossing singers like Joe Williams, Arthur Prysock, and Billy Eckstine ranking as his particular favorites. Rawls also tried his hand at harmony-group singing with schoolmate Sam Cooke, together in a gospel outfit called the Teenage Kings of Harmony. Rawls moved on to sing with the Holy Wonders, and in 1951 replaced Cooke in the Highway Q.C.s. In 1953, when Specialty recording artists the Chosen Gospel Singers swung through Chicago on tour, they recruited Rawls as a new member; he made his recording debut on a pair of sessions in early 1954. He later joined the Pilgrim Travelers, but quit in 1956 to enlist in the Army as a paratrooper; upon his discharge in 1958, he returned to the Travelers and embarked on a tour with Cooke. It nearly cost Rawls his life — during the Southern leg of their tour, the car Rawls and Cooke were riding in crashed into a truck. Cooke escaped with minor injuries, but another passenger was killed, and Rawls was actually pronounced dead on the way to the hospital; as it turned out, he spent five and a half days in a coma, did not regain his full memory for another three months, and took an entire year to recuperate.

When Rawls had recovered sufficiently, he switched to secular music and hit the L.A. circuit with a vengeance, performing in clubs, coffeehouses, and any other small venues that would allow him on-stage. During this period, he also landed his first acting role, a small part on the hit detective series 77 Sunset Strip. In 1962, he was discovered at a coffeeshop near Capitol Records headquarters by producer Nick Venet; at Venet’s request, Rawls hastily recorded an audition tape, and wound up with a recording contract. Later that year, Capitol issued Rawls’ debut album, Stormy Monday (alternately known as I’d Rather Drink Muddy Water), a collection of jazz tunes with backing from the Les McCann Trio. The same year, he supplied the impassioned background vocals on Sam Cooke’s hit “Bring It On Home to Me.” Rawls’ next few recordings for Capitol combined jazz, blues, R&B, and pop in varying combinations, sometimes casting him in big-band settings akin to those of his hero Joe Williams. While the results were often rewarding, it was plain that Rawls and Capitol were still searching for a definite direction.

In the meantime, Rawls was revamping his live act by adding lengthy spoken monologues to his songs; these “raps” served as a platform for the singer to discuss social issues and personal experience, not to mention as an attention-getting gimmick that overrode the noise and bustle of the clubs he performed in. 1966’s Live! captured that distinctive concert presence on a repertoire of mostly jazz and blues (plus a celebrated version of “Tobacco Road”), and proved to be a gold-selling breakthrough hit. However, Rawls found an even more lucrative direction when he made the switch to soul music later that year; his first full-fledged R&B album, Soulin’, spawned his first major hit single in “Love Is a Hurtin’ Thing,” which nearly reached the pop Top Ten and went all the way to number one on the R&B charts before year’s end. 1967’s “Dead End Street” hit number three R&B and won Rawls his first Grammy, for Best R&B Vocal Performance; it also teamed Rawls with composer/producer/arranger David Axelrod, who would go on to a legendary career of his own. A 1969 cover of Mable John’s “Your Good Thing (Is About to End)” was Rawls’ next big hit, although by that time his LP sales had begun to slip a bit; nonetheless, he was still a regular presence on variety shows and on the Las Vegas circuit.

In 1971, Rawls parted ways with Capitol and signed with MGM, where he promptly delivered another one of his greatest successes with “Natural Man.” With its subtle message of black pride, “Natural Man” reached the Top 20 on both the pop and R&B charts, and won Rawls his second Grammy. However, much of the material MGM pushed Rawls to record was too lightweight for the singer’s standards; disenchanted, he left the label in 1972. It wasn’t until 1975 that he caught on with another label, the independent Bell Records, where he recorded an early Daryl Hall/John Oates composition, “She’s Gone.” Unfortunately, Rawls’ version was eclipsed by Tavares’ far bigger hit recording of the song, and he soon left Bell to sign with Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff’s legendary soul imprint Philadelphia International. With Gamble and Huff’s help, Rawls managed to successfully reinvent himself in the lush, orchestrated Philly soul idiom. His label debut, 1976’s All Things in Time, proved to be the biggest album of his career, reaching the Top Ten and going platinum; likewise, “You’ll Never Find Another Love Like Mine” became his biggest hit single ever, topping the R&B charts and zooming to number two on the pop side. Despite Rawls’ general taste for mature, adult music, “You’ll Never Find Another Love Like Mine” was compatible enough with the emerging disco sound to garner substantial dance-club play as well. The follow-up single, “Groovy People,” made the R&B Top 20.

Rawls was a hot commodity once again, and he remained one of Philadelphia International’s most successful artists through the rest of the ’70s. His 1977 LP Unmistakably Lou won him a third Grammy for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance and contained the R&B Top Ten hit “See You When I Git There”; later that year, he continued his artistic and commercial hot streak with When You Hear Lou, You’ve Heard It All and “Lady Love.” The title track of 1979’s Let Me Be Good to You was his last big hit with Philly International, reaching number 11 R&B. The following year, Rawls kicked off what would become a consuming passion for years to come: the Lou Rawls Parade of Stars Telethon, an annual event which eventually raised millions of dollars for the United Negro College Fund.

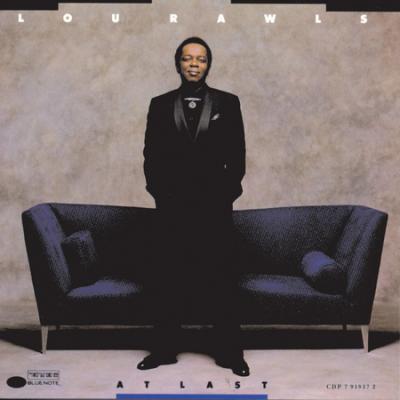

From the ’80s on, Rawls played the part of a well-established entertainer, rather than focusing his energies on maintaining a chart presence. He served a stint on Epic Records from 1982-1986 that proved a commercial disappointment; by then, he was more interested in running the telethon and conducting extensive tours of American military bases around the world. A 1987 reunion with Gamble & Huff produced his final charting single on the R&B side, “I Wish You Belonged to Me.” Toward the end of the ’80s, Rawls made some recordings for Blue Note, including the Grammy-nominated At Last in 1989.

During the latter half of the ’90s, Rawls returned to his acting career with greater frequency, appearing in the acclaimed Leaving Las Vegas (among many other films and TV shows) and also pursuing voice-over work in cartoons like Hey Arnold and Rugrats (he’d begun this side of his career singing on several Garfield specials). Most of his ’90s recordings were holiday collections, but 1998’s Seasons 4 U was a jazzy outing released on his own label. Rawls entered the new millennium by returning to his gospel roots on 2001’s I’m Blessed (astonishingly, his first solo gospel album) and 2002’s Oh Happy Day. In 2003 he paid tribute to Frank Sinatra with the release of Rawls Sings Sinatra on Savoy Jazz. On January 6, 2006, he succumbed to a two-year fight with cancer. ~ Steve Huey